Clean energy galore

Hydrogen from the grasslands

In the middle of the Western and Central Kazakhstan steppes (plenty of wind, hot summers, sunny winters), the German-Swedish company Svevind intends to establish one of the largest production plants for green hydrogen. The total capacity of the wind and solar farms planned for this project is 45 gigawatts (GW), roughly equating to 45 coal-fired power stations. The electrolyzers for hydrogen production are supposed to have a total capacity of 30 GW – enough for producing around three million metric tons (3.3 million short tons) of hydrogen per year that could either be exported to the European and Asian markets through pipelines or used locally to produce ammonia, steel or aluminum. In June, Svevind signed a letter of intent for the project with an investment promotion agency in Kazakhstan. If everything goes as planned, the entire facility will be up and running within eight to ten years.

100 times

the worldwide energy consumption could be covered by wind and solar power, according to the UK think tank Carbon Tracker. If we managed to use nature’s power efficiently, says Carbon Tracker, it would be possible to displace fossil fuels from the electricity sector by the mid-2030s and from energy supply as a whole by 2050.

Green fuels from Australia

With a capacity of 50 GW, the Western Green Energy Hub (WGEH) in Western Australia is supposed to be even a bit larger than the huge Kazakhstan project. The objective here is to produce green hydrogen as well, particularly for processing into carbon-neutral fuels. The WGEH consortium, which includes Morning Traditional Lands Aboriginal Corp. representing the indigenous land owners, expects to produce 3.5 million metric tons (3.9 million short tons) of hydrogen per year. The WGEH extending across a desert area of 15,000 square kilometers / 5,800 square miles (four times the size of Majorca) includes a port so that the hydrogen could be exported by ship. The Western Australian government still has to approve the project – the state recently refused to consent to a similar one. However, since the WGEH is partially located on the coast and said to take environmental aspects into greater consideration, the project owners expect approval.

UPDATE: Singapore wants to use Australian solar power plants, among other things, to achieve its goal of CO2 neutrality. To this end, the Sun Cable company wants to build a 12,000-hectare solar park in northern Australia. Output: 3.2 gigawatts. Batteries with a planned capacity of 36 to 42 gigawatt hours will serve as intermediate storage. The electricity will be transported via a 5,000-kilometer line (of which 4,200 km will be underwater).

Wind power export by cable

The wind blows most consistently on the ocean. Denmark now intends to carry offshore energy production to extremes by planning the construction of an artificial island to which 200 wind turbines with a total capacity of ten GW would be connected. Potentially, around 300 gigawatts of offshore capacity are supposed to be established in the North Sea, which equates to the power consumption of 860 million people. As a result, the European Union with a current population of 447 million would have enough energy to largely cover even industrial requirements. The electricity is supposed to be distributed by so-called high-voltage direct current (HVDC) cables. The currently longest sea cable in the world, the 516-kilometer (320-mile) “Nordlink,” connects Germany with Norway. In October, an even longer line of 720 kilometers (450 miles) between Norway and the United Kingdom is supposed to be activated. It has a capacity of 1.4 GW. The Netherlands (via “NordNed”) and Denmark (via the Skagerrak line) have connected themselves to Norway as well. The hydropower country is supposed to not only supply electric energy but become Europe’s green-power battery as well. Whenever the North Sea wind farms produce surplus electricity, it’s supposed to flow via the bidirectional HVDCs to Norwegian pumped storage power plants that can fill their water reservoirs with a current storage volume of 84 TWh. Potentially, this volume could be increased significantly because many of the roughly 1,250 Norwegian hydropower stations are currently still without a pumping function. They could be converted with a relatively minor investment because they have both an upper and a lower reservoir that’s needed for pumped storage.

Current from currents

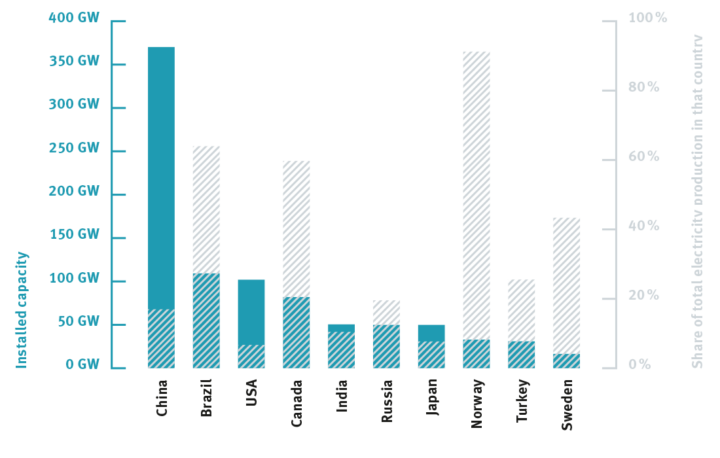

With 4296.8 TWh, which corresponds to a share of 16.02 percent of the worldwide electricity production, hydropower in 2020 was the third most important form of power generation, trailing the conversion of coal and natural gas into electricity, and ranking ahead of nuclear power, according to the Statistical Review of World Energy 2021 published by the energy corporation BP. Forecasts for the coming decades assume that the currently installed capacity of hydropower stations of around 1,300 GW worldwide will increase to 1,700. At the moment, the hydroelectric record is held by the Three Gorges Dam in China that’s also the biggest power plant in the world in general. With its 32 turbines, it produces 22.5 gigawatts and supplies some 100 million people with electricity. The projected capacity of up to 44 GW of the Inga III dam on the Congo River, where the production of green hydrogen is planned, would be nearly twice as much. However, just like the Three Gorges Dam, Inga III is a controversial project. It would require the resettlement of thousands of people and destroy the habitats of numerous animal and plant species. The decision of whether and how the project that’s been discussed ever since the nineteen-nineties will be implemented is still pending.

The 10 biggest hydropower countries

Methanol from geothermal energy

Regions in which geothermal energy boils the groundwater have particularly easy access to renewable energy. The world’s biggest geothermal power station complex “The Geysers” is located about 110 kilometers (68 miles) north of San Francisco. 18 small turbine units with a capacity of 1.5 GW are spread across an area of 120 square kilometers (46 square miles). The energy they generate supplies the Californian counties of Sonoma, Mendocino and Lake with electricity by cable. The world’s biggest single geothermal power station is located in Iceland. Its capacity is 303 MW. The volcanic island covers 90 percent of its warm water and heating water and 26 percent of its electric power consumption by the thermal water that reaches temperatures of up to 500 °C (930 °F) – making it number one in the world. In interaction with hydropower, Iceland produces a surplus of electricity. Because it has not been possible so far to export it due to the island’s exposed location, energy-intensive industries such as silicon-metal and aluminum production have established operations there. Now the Icelandic energy corporation HS Orka is planning to use the geothermal energy of its island to produce hydrogen that together with CO2 is supposed to be processed into green methanol. The plan is to establish a small 30-MW pilot plant to be followed in a second step by “much higher” capacity. Methanol aka methyl alcohol is easy to transport and suitable for versatile uses, for instance as an alternative to diesel fuel in ships. Iceland’s know-how in the area of geothermal energy is an export hit as well because in all regions with tectonic shift such as California and Iceland the Earth’s heat can be tapped profitably. Experts are focused particularly on countries such as Kenya (which already has eight geothermal power stations), Indonesia, the Philippines and Japan as well as European regions like the Rhone Valley in France. Its decentralized presence is another advantage of geothermal energy over conventional energy producers such as nuclear and coal-fired power plants. Therefore, geothermal energy makes sense particularly in developing nations without a country-wide grid, said Stefan Dietrich from the German Geothermal Association (BVG) in an interview with “Deutsche Welle.”