Masterfully morphed

ROAD

Roads reclaimed as living space

Even at this juncture, more than a billion motorized vehicles are traveling the world’s roadways. By 2035, their number is expected to double. Numerous roads aren’t able to cope with this growth. Because they crumble under their daily loads. Or because they can’t grow anymore themselves. The obliteration of such concrete varicose veins may literally have an invigorating effect.

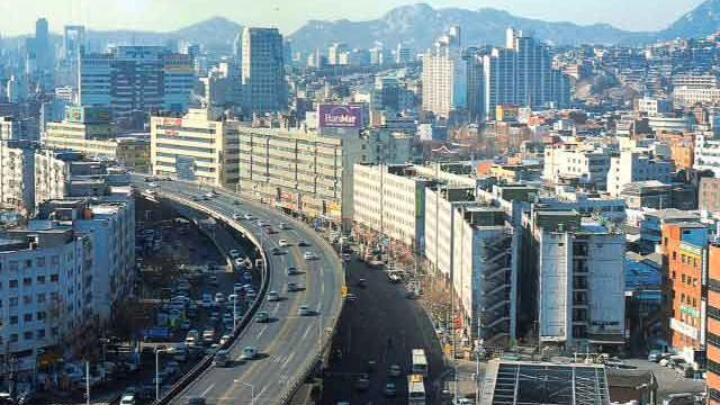

Cheonggyecheon, Seoul

What it used to be

Cracked asphalt, ruptured concrete. Seoul’s city highway had to go. Demolition without reconstruction – this plan met with plenty of approval, but also with protests and even threats of suicide. Many citizens predicted traffic chaos in the light of 168,000 cars per day traveling the 5.7 km (3.54 mi) long four-lane, 35-year-old highway section. Even so, the transformation project was launched in 2002.

What it is now

The demolition exposed the Cheonggyecheon river again that had been covered by the highway, so this body of water was renaturated. Since the project’s completion in 2005, fauna and flora have been thriving there again and so has a new quality of life. The neighborhood, now suddenly turned into a hip place, has been attracting businesses that create jobs and strengthen the economy. In addition, the average temperature along the river has dropped by a remarkable 3.6 °C (38.5 °F). Equally remarkable: The traffic chaos feared by many did not materialize, not least because drivers – more or less voluntarily – switched to public transportation. So, Cheonggyecheon has set an example: in Seoul, where other highways have since been removed, but also for urban planners from other places who’ve been carefully studying this transformati

Embarcadero, San Francisco

What it used to be

The Embarcadero Freeway built in the 1960s used to be regarded as “by far the ugliest site in the city.” For 30 years, the double-decker freeway separated the coastal region and the Ferry Building (pictured) from the city center. In 1989, an earthquake put an end to it. The collapsed blight by the bay was torn down in 1991.

What it is now

A palm-lined boulevard replaced the freeway. Plazas and parks were created and lines of the famous cable car established. Today, the Embarcadero is a popular place for a night walk, Pier 39 west of the Ferry Building one of the city’s central tourist attractions.

AIRPORT

More planes, more space

More and more takeoffs, more and more landings, more and more passengers, larger and larger airports. Aviation is booming around the globe. The number of passengers per year, from four billion in 2017, is predicted to nearly double to 7.8 billion per year in 2036. By 2050, even up to 16 billion passengers are anticipated. In Europe alone, 70,000 scheduled flights are supposed to take off per day by that time. Many airports inside or close to cities are no longer able to keep pace with such growth, not least due to stricter environmental controls, and have to move to the surrounding areas. Some of them already have, like Berlin, Denver, Liverpool, Munich, Oslo and Hong Kong. Runways have been reclaimed there as places to live, work and play.

Tempelhof, Berlin

What it used to be

In 1909, the first motorized airplane took off from the former military parade ground. Scheduled air service started in 1923 and was discontinued 85 years later. The airport terminal that was begun to be constructed in 1936 was the world’s largest building in terms of floor space until 1943. During the Berlin Blockade, planes carrying supplies as part of the airlift would frequently land at Tempelhof at merely 90-second intervals.

What it is now

After aviation operations ceased in 2008, the Tempelhof airfield became an urban recreational area. The impressive terminal including the apron is used by tenants from a wide variety of business sectors and as an event area, for instance as the venue of Team Audi Sport ABT Schaeffler’s Formula E home round on May 19, 2018.

Kai Tak, Hong Kong

What it used to be

The approach over Hong Kong’s street canyons to the Kai Tak airport that was built in 1954 and closed in 1998 used to be one of the most dangerous in the world, not least due to the treacherous wind conditions. That’s why the airport that in the 1990s was the fourth most frequented hub in the world was also dubbed “Kai Tak Heart Attack.” Its successor, located 39 km (24.23 mi) away from the city, is China’s second-largest passenger airport and the world’s largest cargo airport.

What it is now

Ocean liners instead of airliners are now heading for Kai Tak. In 2013, the cruise ship terminal, which cost one billion dollars according to media reports, was taken into operation. On the former Runway 13, golf can be played today. 158,000 trees and shrubs were planted for the Runway Park. For ambitious construction projects, roads were paved and utility lines installed, but the planned buildings have not been erected – yet. Now they’re supposed to become reality and the former airport be awakened to a new urban life with some 50,000 apartments, offices, shops, sports and recreational facilities.

Messe Riem, Munich

What it used to be

When Munich’s Oberwiesenfeld city airport was inaugurated in 1919 it was actually too small even then. An alternative “far away from the city” was needed: In 1939, the first airliner landed in München-Riem. But this airport, as well, was swallowed by the expanding city. As early as in the 1960s, officials started looking for an alternative site even farther away from the city limits and found it in an area called Erdinger Moos.

What it is now

On the Oberwiesenfeld premises, the Olympiapark for the 1972 Games was built. In Riem, a “trade fair city” emerged – the construction project encompassing a residential and exhibition building, a park and a shopping mall was the second-largest one in the city’s history after the Olympiapark. Riem is the venue of the world’s largest trade show: the “Bauma” construction materials and construction machines exhibition. The airport that replaced the one in Riem, the intercontinental Franz Josef Strauß airport opened in 1992, is 30 km (18.6 mi) away from the city or a 45-minute ride on a commuter train.

TRAIN

The line ends here

During industrialization in the 19th and at the beginning of the 20th century, factories mushroomed, not on greenfields like in today’s industrial parks but in the cities. A continuous flow of materials had to be ensured to keep manufacturing operations running. Freight trains proved very efficient for this purpose, so rail networks kept expanding. In the course of further developments, the greater flexibility of trucks increasingly caused cargo hauls to be shifted from rail to road. Furthermore, the growing need for office and residential space forced many larger manufacturing operations out of urban sites. Structures that bear witness to past inner-city freight transportation can still be seen in many major cities today. Most of them are in a state of dereliction, but there are exceptions (see examples at left). Unlike rail cargo, rail-based urban passenger transportation is flourishing – which has consequences as well. In many places, more efficient routes have to be established and more modern stations built. Still, old infrastructure doesn’t necessarily have to be torn down for good. With plenty of creativity new life can flourish in abandoned facilities.

High Line, New York

What it used to be

In 1847, the prospering Meatpacking District, an industrial area in the west of Manhattan, was connected to the rail network by the West Side Freight Line. When road traffic kept increasing at the beginning of the 20th century the train tracks in the streets interfered – in 1932, the Freight Line became a High Line. But as early as in the 1950s, freight transportation was shifted from the elevated railroad spur back onto the road – into trucks. In 1960, an initial section of the High Line was torn down and the last train ran in 1980.

What it is now

The “Friends of the High Line” saved the last 2.3 kilometers (1.43 miles) of railroad history and transformed it into an elevated park. Since its completion, some five million people per year have been visiting the greened tracks in the middle of their creative neighborhood.

Waterloo Station Catacombs, London

What it used to be

In parallel to the continuing expansion of rail-based transportation, London’s central Waterloo Station that was inaugurated in 1848 kept growing as well. In 1854, a curious building was erected adjacent to the main hall on the west: the Necropolis Station from where trains with London’s dead and their mourners would depart for a cemetery on the city’s outskirts. In 1902, the station of the dead moved to the Waterloo south side. Before embarking on their last journey, the mortal remains were kept in the same place as before – the catacomb labyrinth underneath Waterloo Station that had consistently grown as well – until the service was discontinued in 1941.

What it is now

Following the last service of the Necropolis Railway the catacombs fell into oblivion – until the London art scene turned its attention to them after the turn of the millennium. Cultural centers moved into the underworld of the UK’s busiest train station (some 100 million passengers per year): the “Vaults Theatre” on the east side, the “House of Vans” into the Old Vic Tunnels on the west (pictured) including London’s first indoor skate park. Now the idea of transferring the concept to the Mayfair underground station at Hyde Park that has been disused since 1932 is being pursued.

Musée D’Orsay, Paris

What it used to be

The Gare d’Orsay in Paris, inaugurated in 1900, with its elaborate ornaments was too beautiful to admit dirty steam engines, so d’Orsay went down in Paris city history as the first terminus for electric trains. However, as early as in 1939, the station became too small for long-distance trains and after the end of the Second World War no commuter trains stopped there anymore either – the magnificent building was threatened to be torn down.

What it is now

At the end of the 1970s, then President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing personally supported a plan to convert the station into a museum of art from the period between 1848 and 1914. Every year, the exhibition attracts 3.8 million visitors, so making the former train station a busy place.

PORT

New berthing worlds

Due to globalization, world trade has grown by a factor of 19 since 1960 – three times as much as the global economy. And here’s another astonishing figure: 90 percent of the export trade is handled by sea. In parallel to sea trade, the ships have grown as well. A view from the decks of the “Cap San Diego” museum ship to the container terminal at the Hamburg port where the really large vessels berth reveals the differences: The general cargo ship built in 1960 is 160 m (525 ft) long and had a cargo capacity of 10,000 metric (11,023.1 short) tons. The current 400 m (1,312.3 ft) long cargo ships can carry 18 times as much – and only require half the crew. One of the most important game changers of world trade was first dispatched in 1956: the intermodal container. Today, some 30 million of these 20- or 40-foot long standardized metal boxes are traversing the oceans. The world’s largest container vessels – the G-Class of the OOCL shipping company – can each carry 21,413 intermodal containers. These giants of the seas are unloaded in two to three days’ time on highly automated high-tech terminals. Many of the old port facilities around the world were unable to keep pace with the rapid changes in this sector. However, their locations directly on the waterfront make these areas highly attractive for use as residential and business districts.

Hafencity, Hamburg

What it used to be

The Hamburg port, first mentioned in the 9th century and officially established on May 7, 1189, during the course of its existence continually expanded from a berthing place in the old town on the northern banks of the Elbe river toward the southwest. Since the 1970s, container vessels have been the dominant sight while importance of the northern part of the “Speicherstadt” (warehouse district) kept diminishing and large areas were no longer used.

What it is now

In 2001, the ground was broken for the new HafenCity, currently Europe’s largest urban development project covering a total area of 157 hectares (388 acres). After completion of the development with a university, a shopping mall, schools, childcare centers, offices, residential buildings, subway stations, the conservation of the old warehouses, a skyscraper and, naturally, the world-famous “Elbphilharmonie” concert hall by 2030, 120,000 people are expected to live and work in the district.

Kraanspoor, Amsterdam

What it used to be

The Dutch metropolis of Amsterdam has been a port city since the 13th century. Complex work on canals kept opening up new paths to the North Sea. In the 1950s, the western part of the port was extended which caused the importance of the northern and eastern sections to diminish.

What it is now

In 1990, the abandoned areas began to be transformed into living, working and recreational spaces. A particularly intriguing example of the development there is “Kraanspoor,” an elevated office building (270 m/885.8 ft long and just 13.5 m/44.3 ft wide) erected 13 m (42.7 ft) above water on top of an old crane-way. A particularly unusual feature is that employees can go to work by boat, berthing immediately next to the building.

Water turns into air

London pursued a different path. In the area of the former “King George V Dock,” the London City Airport was built. While other city airports are closing, the one on the Thames is growing: a redevelopment project is planned to increase capacity to eight million passengers per year.