One thing after the other

They seemed to be unstoppable. Ever since they were invented, assembly lines have been running untiringly, shortening manufacturing cycles and material hauling distances. They’ve been saving time, space and money. In the course of decades, mass production on assembly lines has consistently been streamlined, standardized and perfected – and propelled industrialization into a new dimension. To achieve this, the lines have been moving along at an increasingly accelerated rhythm, diligently, unrelentingly, and dehumanizing work in the process, because workers became helping hands to machines that set the pace and forced them to do the same monotonous things over and over – day in day out. However, the splitting of work into individual segments didn’t start with the modern assembly line but centuries earlier.

Assembly lines have been around for 500 years

The pilot run of mass production split into individual process steps did not start with Henry Ford as many of us might think, but much earlier – in the late 15th century at the Arsenale Novissimo shipyard in Venice. It’s assumed that there the first ships were built by workers assembling standardized components in a form of line manufacturing. In this way, one sailboat per day was purportedly launched.

What an efficient system – and all of it without the help of wind or water mills, steam engines or electricity that would later give industrial manufacturing a real boost.

Two sides of the Fordism coin

Even though Henry Ford ultimately just adapted existing manufacturing technologies to his needs he’s deemed to be the “father of the assembly line.” He’d adopted the idea from the world’s largest meat factory, the Union Stock Yards in Chicago, where livestock were suspended from rotating conveyor chains called disassembly lines: disassembly vs. assembly. But be that as it may, on October 7, 1913, Ford’s factory at Highland Park in Detroit started a pilot run of his first moving line for the production of the “Model T.” Since then, this date has been regarded as the beginning of the moving line – and of Fordism – a synonym for soulless mass production decisively coined by Antonio Gramsci, a Marxist intellectual. Not to be forgotten in this context, though, is the fact that Henry Ford not only increased production eight-fold, but in doing so drastically reduced the price of his “Tin Lizzie” from 850 to 370 U.S. dollars. Suddenly larger parts of the population were able to afford their own four wheels, which rang in the era of personal mobility for everyone.

7.2 km (4.47 mi)

is the length of the world’s longest conveyor belt. At a dizzying height in Barroso (Brazil), it moves 1,500 metric tons (1,650 short tons) of calcium silicate brick per hour above trees, hills and roads. The humongous belt replaces 40 trucks per hour.

This was particularly true because the wages of the line workers clearly increased, too. In 1914, Ford doubled the daily pay of his workers to five dollars and claimed that the Fordian principles had the potential of putting an end to poverty. In fact, a major portion of the workers’ wages was spent on consumer goods, which served as a lubricant for the moving line of economic growth. However, Ford wasn’t quite the benefactor he’d often tout himself as, because he only raised his workers’ wages out of sheer necessity. In the early days of his line manufacturing operation, they’d run from his factory halls in droves. The demotivating monotony of line work caused personnel turnover to skyrocket to 90 percent. Peace and loyalty only moved in when Ford raised his workers’ wages and introduced eight-hour days with a three-shift schedule.

However, a fundamental problem of assembly line work remained. “Bis repetita non placent” – repetitions are unpleasant, as the Roman poet Horace already knew in his day. Another point of criticism is the lack of satisfaction that comes from holistic creation. Because all you do is turn a screw or two, like Charlie Chaplin in his movie “Modern Times.” Ford and those who copied him swept the issue under the money rug where it’s been fermenting ever since.

In socio-critical Sweden, Volvo, in 1973, made a bold move against Fordism. At its Kalmar plant, the automaker announced its departure from assembly line work – not least driven by the looming threat of a strike wave as well as high personnel turnover and sickness absence rates. At the Uddevalla plant that was opened in 1989, the fulfilling principle of holistic creation was adopted as well: a team put together a complete car in the final assembly stage. Even though the productivity of both plants was deemed to be competitive for a long time, both were shut down. Volvo explained the decision by saying that without repetitive work higher levels of automation could not be achieved at the plants and that, consequently, they no longer had a viable economic future. The irony of this industrial story: In 1999, Ford swallowed Volvo’s troubled passenger car division. Today, Volvo is a Chinese company.

Perfect monotony machines

Robots are perfectly suited for automating repetitive work. “Robot” is the Czech word for “servitude” and “drudgery.” The automatic toiler doesn’t mind monotony, goes about its work without stopping or complaining, but with efficiency, precision and speed, and does so 24/7: the perfect partner for assembly lines. In 1961, the first industrial robot, the Unimate weighing 1.8 metric tons (2.0 short tons), installed die-cast elements on car doors at a General Motors facility.

Robots and humans hand in hand

Today (not only) car factories are full of robots. Let’s take SEAT’s parent plant in Martorell near Barcelona, for example, where cars were still painted by hand up until the 1970s. Today, 84 robots apply the paint in a spray booth. More than 2,000 robots are employed in the metal shop and 125 autonomous robots in the assembly hall. Although that’s an awesome number in total they’re still a minority because more than 7,000 human colleagues are working side by side with them.

Side by side is a phrase that can increasingly be taken literally. While industrial robots used to be confined to cages, they’re now allowed to work in the context of Human-Robot Collaboration (HRC). The electrical colleagues of humans have also received a new name. The collaborating robots that increasingly often can be seen right next to the conventional line worker are called cobots. Their purpose is not to replace humans but to relieve them of monotonous and physically strenuous jobs.

The fact that hard times are in store for the assembly line at least in automobile production is attributable to the increasing customization of this mass product. Henry Ford’s witty remark that a customer can have a car painted in any color as long as it’s black has long ceased to be relevant. Thanks to endless lists of options even bread-and-butter cars can be configured to become one-of-a-kind. Such levels of customization cause even the best assembly line to stall. A modular, intelligently controlled assembly process using mobile robots instead of a moving line to deliver the material to the assembly stations just in time can handle this in much better ways.

In the light of such developments, the notion that, of all things, the customer’s wish for greater variety might put a stop to the monotony of the assembly line – at least in automotive manufacturing – is indeed intriguing.

Expert know-how

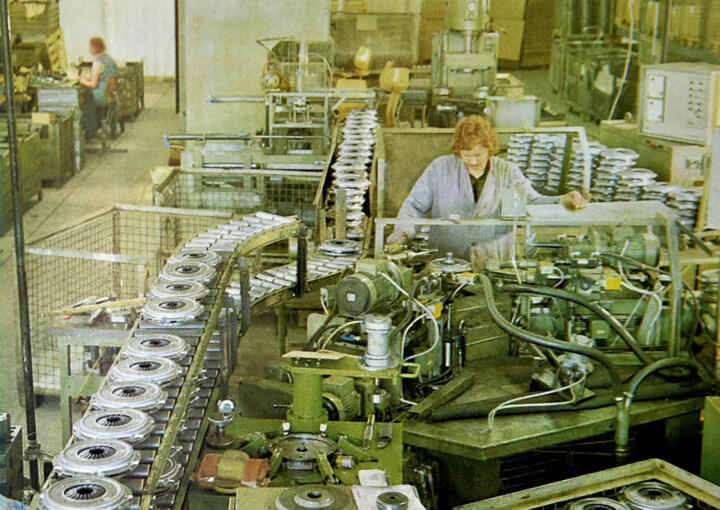

One of Schaeffler’s fortes is the company’s production know-how developed in more than 120 years.

A perfect example: UniAir. The idea of the fully variable valve control system was conceived at the Fiat Development Center RCF. However, the expertise in developing the system to market level, industrialization and manufacturing was lacking there. Schaeffler’s experts have been contributing it since 2009.

The Schaeffler Group supplies high-quality products to more than 60 sectors in total – with a commitment to “zero defects.” In addition to a standardized worldwide quality management system, Schaeffler relies on close collaboration between product and production specialists in this context.

Special-purpose machinery has been one of the traditional fortes of the Group. If Schaeffler’s exacting expectations cannot be met by a production machine that’s available on the market the machine will be developed and produced in-house. No matter whether a product is made in-house or purchased, Schaeffler has a tradition of incorporating state-of-the art technologies in its manufacturing operations. Included already or planned for the near future are additive manufacturing (including 3D printing etc.), lightweight design, work with digital twins, collaborative robots (cobots) and autonomous production. However, new technologies don’t necessarily have to replace time-tested ones. According to Schaeffler’s experience, a combination of both may well prove to be the best solution.