The long road to the modern city

The original reason why humans permanently settled down and cities evolved can be found – in the country. The ability to grow crops and raise livestock made it possible to feed many people in one place. Humans became sedentary. Settlements were established, expanded and turned into towns. But as populations grew, so did problems. Johann Peter Frank, a physician in the Franco-German border region, in 1790 made the famous statement: “Most of the ills that plague us stem from humans themselves.” They include garbage, dirt and diseases.

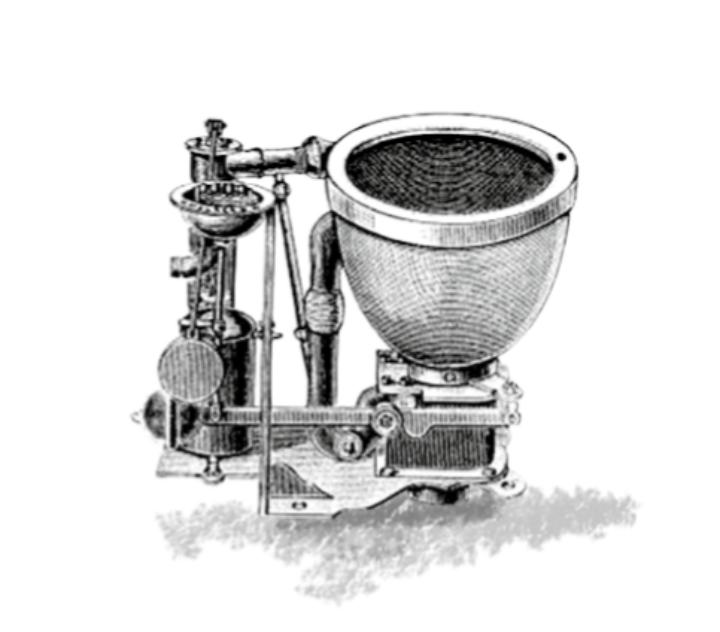

11 aqueducts

supplied Rome with fresh water in the 2nd century AD. The main sewage system, the Cloaca Maxima, was a 3 meter (9.8 feet) wide, 4 meter (13.1 feet) high canal that has been preserved to this day with its outfall into the River Tiber – as shown in this drawing. Other Roman settlements such as Cologne, Trier and Xanten had similar water supply and sewer systems.

Some of the early advanced civilizations already had water supply and sewage systems – achievements that would subsequently characterize many cities in Greek and Roman antiquity as well. The ancient Sumerians in today’s Iraq are said to have even had toilet rooms with flushing systems. However, in the Medieval Period, much of the knowledge from antiquity was lost again. In his article “Hygiene und Öffentliche Gesundheit” (“Hygiene and Public Health”) Martin Exner explains that the average life expectancy at the beginning of the 20th century was about 45 years – equating roughly to that of a Roman 2,000 years ago. This shows how advanced people in antiquity were in terms of sanitation.

City life and sanitation – a dichotomy with a long history

When looking at the conditions in medieval cities low life expectancy comes as no surprise. Nobles and servants alike grossly neglect sanitation and personal hygiene. Livestock typically dwell in the same four walls as humans. Clean water is in scarce supply and, due to the misbelief that water might penetrate the skin through the pores and thus cause serious diseases, washing is reduced to a minimum. The consequences of this lack of hygiene are epidemic diseases such as the plague, smallpox or cholera.

In 1596

John Harington, commissioned by Queen Elizabeth I, invented the first flushing toilet. His contemporaries, however, thought the unusual contraption was a joke, so his invention sank into oblivion for nearly 200 years.

Only in the High Middle Ages do water supply and sewage systems gradually return to the cities. In 1596, the Englishman Sir John Harington comes up with the revolutionary design of a flushing toilet with a tank and flush valve – the first example of modern sanitary engineering, albeit one that won’t be followed by others for a long time. The common people continue to live in deplorable conditions much longer. In the 18th century, Johann Peter Frank writes: “In a very large number of houses, there are no privies at all and certain containers are used for each family so long as this is possible. The place where all excretions are collected is either a dung heap enclosed in the narrow yard or perhaps even the public street.”

Only in the 19th century, many big cities issue stricter regulations. Yet 2.3 billion people are still living without basic sanitary systems today, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Plastic bags are a popular, albeit poor substitute for toilets in the world’s slums. The bags either end up on the side of the street or on the roofs of houses which, ultimately, endangers human lives: 3.5 million people per year die from diarrheal diseases. Creating basic sanitary systems is one of the most urgent challenges faced by growing metropolises in poorer regions.

3 cents

is the cost of “Peepoo,” a toilet bag invented in Sweden, which makes the waterless disposable toilet affordable even for people who live in slums. A mixture of chemicals in the bag kills all germs and transforms human excretions into fertilizer within a few weeks. Thanks to its usefulness for farming the fertilizer can even be sold. The bag itself is biodegradable and dissolves within a year without leaving any residues.

Education is a child of the city

Let’s turn to another aspect of urban life: education. The idea of schools is older than one might think. The first known record of a school is found on an Egyptian epitaph written some 4,000 years ago. In ancient cities, entire educational systems emerge: Teachers provide lessons against remuneration on market squares, in backyards or in the private mansions of rich citizens and they usually don’t treat their pupils with kid gloves. In recorded memories of school, the poet Horace describes his teacher, Orbilius Pupillus, as “fond of flogging.”

This early educational system, however, is a far cry from education for the masses. Estimates assume that a tenth of the population gets to enjoy it. And the number of those who do dramatically drops with the collapse of the Roman Empire. In the Medieval Period, cities are no longer the main places of learning. They’re now primarily found in abbeys where the libraries from antiquity are hoarded. The more than 2,000 scripts that have been preserved in the Abbey library of Saint Gall in Switzerland founded in the 8th century bear witness to this. The importance of education only changes again when at the end of the Middle Ages new cities are founded and the ideas of antiquity are rediscovered. In many cities, grammar schools and universities are established.

The art of printing buds in the city

The most important pioneer of printing is the son of a merchant in Mainz, Germany. In the middle of the 15th century, Johannes Gutenberg develops a technique for making type pieces that can be individually cast and arranged quickly. Movable type is an invention that propels humanity into a new era and restores the former role of cities as centers of learning. By 1500, as many as 252 cities have printing shops. This is where books, and subsequently newspapers, are produced and the majority of their readers are found. American media theorist Neil Postman fittingly put this development in a nutshell: “If the telescope was the eye that gave access to a new world of facts and new methods of obtaining them, then the printing press was the larynx.”

Subsequently, education becomes systematized, frequently starting at urban universities. In the 17th century, Johann Amos Comenius, a Czech pedagogue who also studied in Heidelberg, Germany, advocates mandatory schooling for everyone, irrespective of social origin and gender. His idea catches on. Austria’s empress, Maria Theresia, introduces mandatory schooling as early as in 1774. However, in spite of all the decrees issued by local rulers, school only begins to reach all children in the course of the 19th century – and clearly more effectively in the city than in rural regions where in village schools for all grades a single teacher may teach as many as 100 pupils of various ages. The curriculum is more varied in the city as well. In almost all countries of the world there’s still an achievement gap between students in urban and rural areas, according to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). A larger and more reliable educational offering and a more varied cultural and social environment speak for the city, according to PISA.

1,421 years

old is the oldest school in the world that has continuously been providing education until today. It is the King’s School in the English city of Canterbury.

The education offensive driven in the 18th and 19th centuries primarily in the cities ultimately, if not earlier, pays off when factories emerging in the course of industrialization create a high demand for skilled workers. Educational institutions have evolved over centuries into an important element of urban identities: The high-tech location of Silicon Valley for instance originated as Stanford Industrial Park right next to the famous university in California. Many of its graduates started their own businesses there.

Smog as a next-door neighbor

A third aspect without which modern cities are inconceivable is the way in which the previously mentioned industrial revolution has influenced them. The invention of the steam engine in the 18th century makes manufacturing independent of the locations of raw material supply and moves it into the cities – followed by millions of rural residents looking for work. In the 19th century, the population of London skyrockets to seven times its previous number. Slums emerge. The city becomes dirty and loud. “A sort of black smoke covers the city. The sun seen through it is a disc without rays … A thousand noises disturb this damp, dark labyrinth …” This is how the Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville describes the industrial city of Manchester in the 1830s. Billowing smokestacks, freight trains thumping through residential areas, the factory turns into a next-door neighbor. Due to industrialization, the city also develops a different sense of time than people are accustomed to in rural regions. The rhythm is no longer driven by sunrise and sunset. Factory owners enforce their ideas of punctuality by means of minutely detailed schedules and supervisors. And even today, the old wisdom that the clock ticks differently in the country is still true.

One after the other, smokestacks grow into the sky in the heyday of industrialization – and social divides widen: “While more and more people flocked to the city, the rich bourgeoisie moved to the outskirts,” explains Bernd Kreuzer, who conducts research into the history of technology at RWTH Aachen. “Good” and “bad” neighborhoods emerge. “Today, you can see in many European cities that the better residential areas are located in the western part of town. The reason is that the predominant weather conditions would blow emissions toward the eastern part.”

What was separated is growing together again

In the 20th century, cities become even more radically structured. “In contrast to the previous mix of commerce, manufacturing and housing, the central modern-day idea of urban planning featured a strict separation of urban districts according to function,” Kreuzer explains. The distances between residential neighborhoods, industrial areas and office districts are overcome by an invention that literally marks a breakthrough – the automobile.

The evolution of technology makes city air cleaner again. Environmental legislation emerges in the 1960s. In the United States alone, in addition to 27 laws, hundreds of environmental regulations are passed between 1969 and 1979. Many industrial nations are reducing sulfur-dioxide emissions to curb acid rain and tree decline. CFCs are identified as the gases that cause the ozone hole and subsequently banned. However, many “reported successes” only show how bad the situation still is: at the beginning of 2018, Beijing was without smog for five weeks – a sensation!

The greatest challenge that has come in the wake of industrialization is the current battle against climate change. The use of fossil energy carriers is reduced and its efficiency enhanced. Digital transformation and artificial intelligence are shaping the new, connected metropolises. Old concepts of urban life are abandoned. “The compact city” in which the places for living, working and shopping are close together is now in vogue again. The city – any city – was, is and will remain an incomplete project.