Grandpa’s Journey to the Moon

The “unsinkable” Titanic had not yet hit an iceberg and hardly anyone suspected that the first modern war was going to set Europe and the world on fire. Instead, wireless technology invented by the Italian Guglielmo Marconi was transmitting increasingly incredible news across the Atlantic: about the motorized flights of the Wright Brothers in Kitty Hawk or the blessings of the electric tungsten incandescent light bulb invented by the American Thomas Alva Edison, to name just a few. As far back as in 1895, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen had managed to look inside the human body by means of X-rays aka Röntgen rays while research scientists such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch laid the foundations for modern microbiology using microscopes. In 1898, the physicists and married couple Marie and Pierre Curie had discovered radium that would soon become acclaimed as being able to cure virtually any disease due to its beneficial radiation and – in sufficiently high dosage – even put an end to aging and death. Meanwhile, German cavalry general Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin lent wings to the high-powered dreams of a whole nation with his rigid airships made of cotton, aluminum and the intestines of cattle. With that, the force of gravity seemed to have been overcome once and for all.

Some utopian dreams became reality

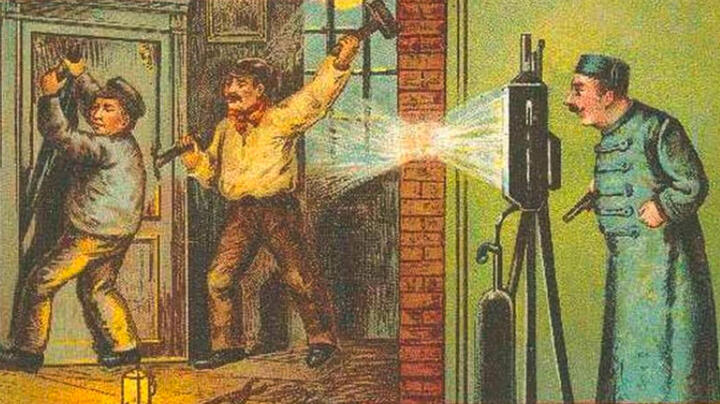

In keeping with the euphoria of the times, scientists and the still young genre of science fiction novels, as well as the illustrators of the collectible cards added to chocolate boxes that were highly popular at the time, painted a bright picture of the year 2000. The Berlin-based cocoa factory Hildebrand (subsequently known for its caffeinated Scho-Ka-Kola chocolate brand) saw law enforcement officers of the future hunting down criminals using portable X-ray devices to peek through walls. Today, reality has long caught up with such fantasies. The Hamburg Customs Authority, for instance, has been X-raying shipping containers to put a stop to the game of criminal smugglers since 1996. The first 20 years reflect the following statistics: in total, more than 1.5 billion untaxed cigarettes, 2,700 weapons and ammunition, 38,000 kilograms (83,770 lb) of marihuana, 13,200 kilograms (29,000 lb) of hash, and 4,600 kilograms (10.140 lb) of cocaine were confiscated – identified by just one stationary system. The observation of suspects through walls as shown in the pictures on little chocolate cards has been possible for a long time, too – thanks to sensitive thermal imaging cameras.

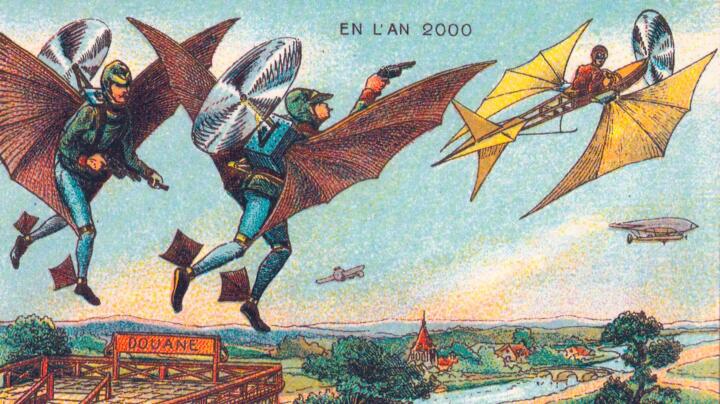

But let’s go back to the utopian dreams of the past: Fire fighters depicted on a French postcard series (En L’An 2000) equipped with bat wings would fly to the scene of the blaze, while border patrol officers accelerated by propellers on their back would hunt down smugglers. These visions have become reality, too. Dubai equips its fire fighters with jetpacks designed to enable them to rescue people from burning skyscrapers. The emirate’s police force is also supposed to become airborne, by means of hoverboards, while fighting crime with unmanned aerial vehicles aka drones has already become routine practice.

If you want to read the future you have to scroll in the past

André Malraux, French writer (1901–1976)

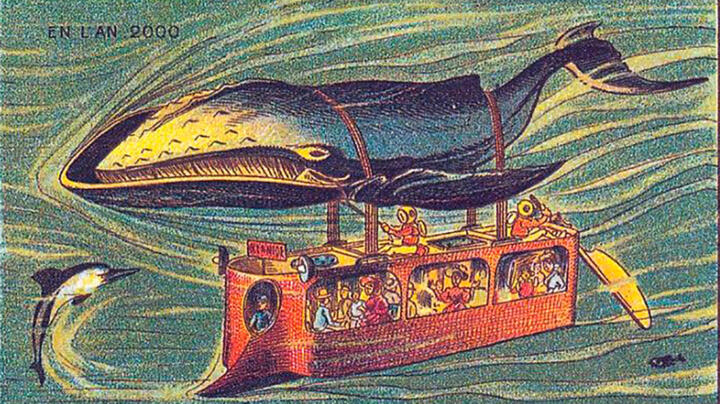

In the area of mobility, utopian thinkers have demonstrated visionary powers as well – even though some of their ideas got stuck in the world of fantasy: Back in those days, global distances had shrunk into short commutes, a suspended monorail train would provide a daily shuttle service for business travelers from Berlin to Cameroon. Those having to cross the Atlantic on business would take the subsea “whale bus” or the practical maritime railroad across water and land, whose trains seamlessly glided from the waves onto the train tracks. And people with an even greater zest for travel would hop on a motorized flying taxi to the Moon and back (header picture) at night.

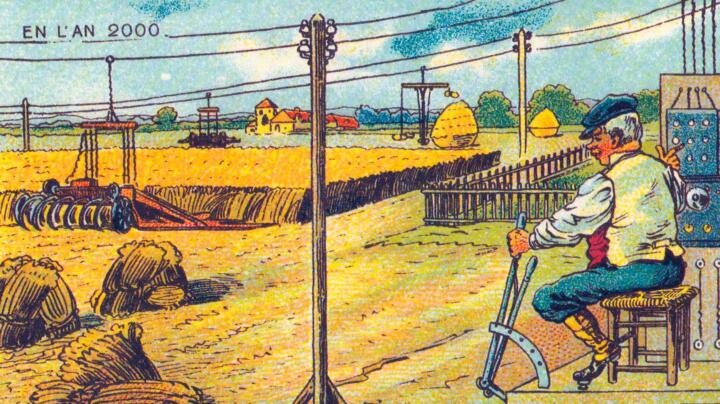

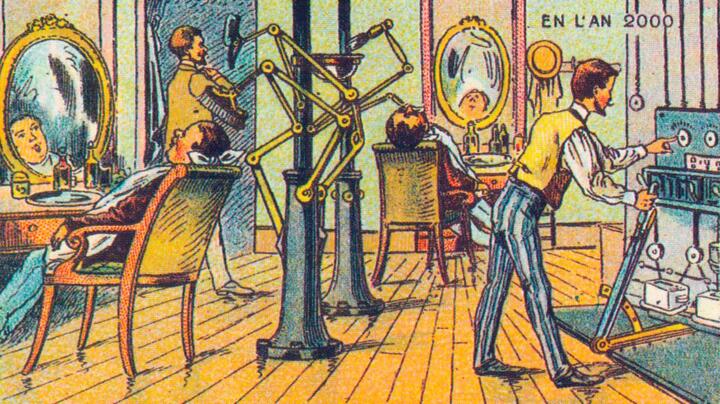

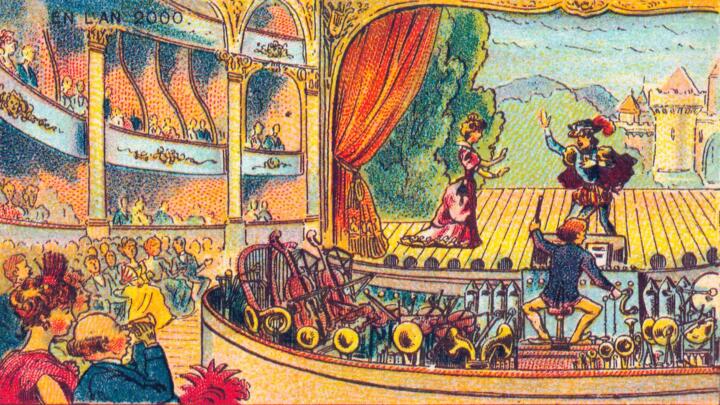

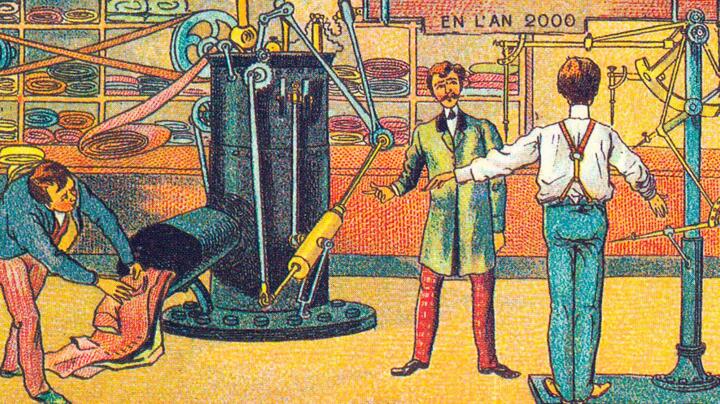

Meanwhile the farmer of the year 2000, while sitting on his porch, would direct an armada of harvesting machines through his fields using the toggles of a remote control device. In this case, autonomous agricultural machines and robotic farm hands have long become reality, too. Another example of a vision-turned-reality is the tailor next-door producing a custom suit from a steam-powered 3D printer with a flick of the wrist. By contrast, the vision of a conductor directing the performance of a robotic orchestra has still remained a utopian idea. And will a robot ever replace a barber? If so, then it will no doubt differ from the illustration in the French postcard series where a barber was operating an early forebear of a modern industrial robot that would almost tenderly move the shaving brush and razor across the cheeks of trusting clients. However, this whole operation seems far more complicated than the barber having done the job himself. Or could it perhaps be that this card doesn’t mean to depict the anticipation of a desirable future at all, but questions whether it makes sense to use a machine?

Visionary acceleration

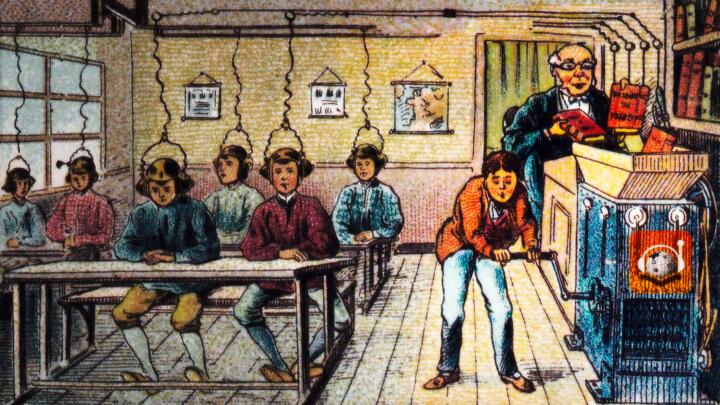

Common to all the utopian ideas of those days is an awesome zest for motion and acceleration that define the working world of an imagined future anticipated by farsighted visionaries. While just 70 years earlier the first railroads had still been rejected in Europe for fear that their awesome speed of 20 and more miles per hour might harm the lungs of passengers and traumatize innocent bystanders on neighboring roads, speed is now seen as a positive across the board. Even school has become a high-speed learning factory in which the teacher throws stacks of books into the hopper of a learning machine that hammers the writings of Horace and Euclid into the students’ brains in record time using a flow of electrons.

In spite of a few amusing misses, the far-sighted accuracy with which the illustrators who created these utopian pictures visualized the future is amazing. Or vice versa: the accuracy with which progress has fulfilled the hopes and expectations of the people who lived one hundred years ago.